Honoring Ancestry: A Time for Remembering

A few thoughts and simple ways to remember your ancestors during Pitru Paksha

As long as I can remember, I’ve been interested in my ancestry. It’s strange to think a family of homesteaders from South Dakota (my family’s original farm was not too far from the one described in some of the later Little House of the Prairie books), who originally hailed from the British Isles, Holland and Bohemia, would merge with a family of Volga Germans from Nebraska and the result would be, well, me. And my daughters. And my unborn grandchildren I can’t wait to someday (hopefully!) meet.

And this is only the 19th/20th/21st century ancestors and family I’m talking about. Who knows the names, stories and lives of the long forgotten dead?

This love, awe and fascination for my ancestral line makes me especially value Pitru Paksha.

What is Pitru Paksha?

Also known as Shraadh or Mahalaya Paksha, Pitru Paksha is a 16-day period dedicated to honoring your ancestors. This period typically falls in the lunar month of Bhadrapada (September–October); in 2023 it will take place between Friday, September, 29 to Saturday, October 14.

The word “Pitru” translates to “forefathers” or “ancestors,” and “Paksha” means “fortnight” in Sanskrit. It is believed that during this 16-day lunar phase, the spirits of the deceased return to the realm of the living to seek blessings and offerings from their descendants.

Ways to Honor Ancestors during Pitru Paksha

Tarpana (offering water): A traditional and fundamental ritual during Pitru Paksha is Tarpana, where water and milk mixed with sesame seeds are offered to the departed souls. This act symbolizes purification and nourishment for the ancestors’ souls.

Food offerings: Preparing and offering food to the departed is a common practice. This “Pind Daan” or “Shraadh” involves offering cooked rice, lentils, and other vegetarian dishes on a special plate. It is believed that the souls partake of the essence of these offerings. In general, it is traditionally advised to refrain from eating meat or drinking alcohol during Pitru Paksha.

Donations: Making charitable donations during Pitru Paksha is seen as a virtuous act. Donating clothes, food, or money to the needy is believed to earn blessings for both the living and the deceased.

Visiting ancestral sites: Pilgrimage to ancestral place or places of significance to your ancestors is a meaningful way to connect with your roots and offer prayers. This can be as elaborate as visiting your great grandmother’s home town in another country or as simple as going to your late uncle’s favorite restaurant.

Caring for elders: Respecting and taking care of elderly family members is a living testament to the values passed down by ancestors. Their well-being is an important aspect of honoring the past.

Meditation and inward reflection: Inward reflection and meditation can help your connect with their ancestral lineage on a deeper level, fostering a sense of gratitude and reverence. Pitru Paksha would also be the ideal time to set up a simple (or elaborate) ancestor altar to work with going forward.

A few more traditional dos and don’t include feeding crows, ravens, dogs, cats and cows (a big do) and refraining from buying clothes, jewelry and cars or cutting your hair and nails (a big don’t).

Here’s is a useful short video from Dr. Robert Svaboda about offering Tarpan during Pitru Paksha.

Even if you aren’t Hindu, Pitru Paksha is a beautiful time to consciously honor and thank your ancestors, as well as ask for their guidance and blessings.

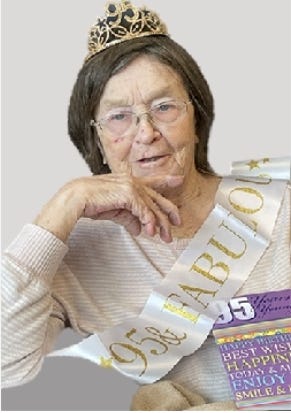

This Pity Paksha, I will particularly be think of my grandmother, who passed away in June at the age of 96.

A few weeks ago, my family had a memorial service for her in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and I was luckily able to fly out from Berlin. At the service, my siblings, mother and I met up aunts and uncles and cousins, many of whom I hadn’t seen in years, and celebrated my grandmother’s life together.

Two of the things my grandmother always told everyone she met was that she had 20 brothers and sisters and she used to have to cook for all the hired hands, both of which were true.

Volga Germans tended to have big families — the more kids you have, the more help you had on the farm–and my grandmother already had ten brothers and sisters when her mother died in a car accident. Her father later remarried a widow who had ten children herself, hence the 21 kids.

When I was younger I used to wonder if my great grandparents ever saw a neighbor kid playing in the yard and had to think hard about whether or not it was one of theirs.

As for cooking for the hired hands, my grandmother married at 18 and suddenly had to feed all the farm workers on her husband’s farm, not to mention her children, who were soon on the way.

In many ways, my grandmother’s life was harsh: poverty, hard work, the Depression, staunch Protestanism. And yet, she was one of the most loving people I’ve ever met: a woman who could make wonders with her hands, whether crafts or krautburgers or cookies, who loved children with all her heart, and unofficially adopted a few needy strays over the years.

RIP, Esther Irene. You will be missed.